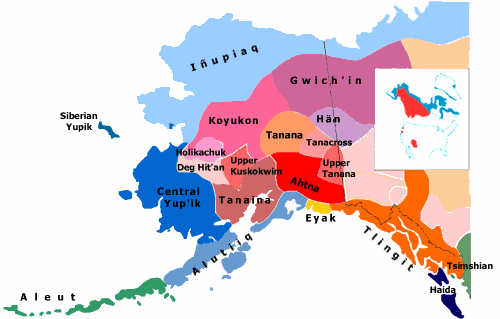

The Inupiaq language is spoken across Alaska’s Arctic costal area (see the language map below).

Language map of Alaska 阿拉斯加的原住民語言分佈

It is closely related to the Canadian Inuit dialects and the Greenlandic dialects. The population of Inupiaq people in Alaska is 15,700 persons, whereas the population in Canada and Greenland is approximately 30,500 and 47,000 persons (Alaska Native Language Center). Inupiaq language is more than 8,000 years old (Browers, 2010: 5).

The contemporary written Inupiaq uses the Latin alphabet. However, if we trace back to the beginning of 20th century, Inupiaq writing started with a pictographic system adapted from the Yupik system of Helper Neck (Kaplan 2005: 235). It was not until the late 1940s that the Inupiaq language was developed for religious purposes. “Hymnals and later the Inupiat New Testament (in 1966) were published, followed by the Inupiat Eskimo Dictionary in 1970.” (ibid).

The Inupiaq people in Alaska are mostly from the Northwest Arctic and North Slope boroughs and the Bering Strais region (IC Magazine). On the one hand, North Slope Borough in Alaska is home to many Inupiaq people. Most of the Borough’s 9000 permanent residents live in eight communities and the Inupiaq people are the majority of every community. The Inupiaq people made up 61 percent in Barrow, 83.3 percent in Anaktuvuk Pass, 88 percent in Kaktovik, 88 percent in Point Lay, 89 percent in Point Hope, 90 percent in Wainwright, 92 percent in Nuiqsut and 92.3 percent in Atqasuk (North Slope Borough). On the other hand, the population of the Northwest Arctic Borough is about 7300, of which approximately 83 percent are Inupiaq people (Browers 2010:4).

The singular noun Inupiaq refers to a person or the language, while the plural Inupiat is often refer to the group, although some prefer Inpiaqs, with the English plural (Kaplan 2001: 250). ’Inuk’ means ‘person’ and -piaq means ‘genuine’. Inupiaq is often spelled as Iñupiaq in northern dialects (Alaska Native Language Center).

In terms of official recognition, Inupiaq language, along with other Alaska’s Indigenous languages, became official language of the state in 2014 (Quinn 2014, Oct 23). It was a powerful move and sent a message that indigenous languages are important (ibid). However, it was also noted that this law “deliberately remains symbolic, featuring a provision that does not requires the state or a municipal government to conduct business or government activities in languages other than English”. Indigenous elders feared that the symbolic action may contribute to real consequences. Eyak, one of Alaska’s indigenous languages, became extinct with the death of its last fluent speaker, Marie Smith, in 2008 (ibid). Ronald Browers, an Inupiaq elder, activist and language teacher, reflected warily on the extinct of Eyak “While it is preserved in books and dictionaries the spoken Eyak language died in January of 2008. No more….gone forever. Perhaps we need to use words like revitalize and grow, and take control of the destiny of our Iñupiaq language so we and it does not face the same destiny of the Eyak language and we fade into oblivion only to be remembered in books and dictionaries. ” (Brower 2010: 4-5).

The Inupiaq language is in danger. According to the Expanded Graded Intergenerational Disruption Scale (EGIDS), Inupiaq language in Alaska is categorized as ‘6b threatened’ (Alaska Native Language Center). Accroding to Joshua Fishman’s threatened language assessment grid, Inupiaq is threatened by the dominant English language. There is no media nor services offered in Inupiaq language. The language proficiency is not a requirement in making the educational curriculum. Even in the families Inupiaq is not spoken necessarily (Brower 2010). Despite of the official status of Inupiaq language, the government approach showed that “Inupiaq language is in some way not as legitimate as the dominating English language” (ibid: 9). Of the 13,500 Inupiat in Alaska, about 3000 persons speak the language. This number is alarmingly lower compared to its Canadian and Greenlandic counterparts. The Canadian Inuit population has 24,000 speakers in the population of 31,000 and there are 46,000 speakers in the population of 46,400 in Greenland (Alaska Native Language Center). In the Northwest Arctic Borough, it is pointed out that of the 83 percent, 6060 Inupiaq people in the Northwest Arctic Borough, “there are now about 1090 fluent Inupiaq first language speakers, making language speakers at 11 percent of the population” (Browers 2010).

Knowing the Inupiaq language is seen as essential for Inupiaq identity (Kaplan 2005). The North Slope Elders has compiled the Northwest Arctic list of values, where language has its first place on the list. This echoes with the three-level theory of culture, where “language is inextricably tired to the first level of culture—how people knows, believes, thinks, and feels. It is a key part of what gies a people their identity.” (Fagan n.d.:10) The revitalization of the Inupiaq language is urgent, but the progress is impeded because Inupiaq people do not seem to have control over the social systems (Ronald Brower, personal communication, February 19, 2016).

“Kisima Inŋitchuŋa” (“Never Alone”) is a video game based on an Inupiaq legend. It is made with the determination to revitalize the Inupiaq language. The game’s trailer is narrated by Ronald Brower, an Inupiaq language teacher at the Alaska Native Language Center at the University of Alaska Fairbanks. Here is the trailer https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=qbRqqPRgBRA

Reference

Alaska Native Language Center http://www.uaf.edu/anlc/languages/i/

Brower Ronald H. (2010). From a Heritage Language to a First Language: Revitalizing the Inupiat Language. In North Slope Inupiat Youth and Elders Conference. Barrow, Alaska November 17-19, 2010.

Fagan K. (n.d.) Identity and Language. Module 2 of Circumpolar Studies 322.

Kaplan L (2005). Inupiq writing and International Inuit Relations. Études/Inuit/Studies, vol. 29, no.1-2. Retrieved from https://www.erudit.org/revue/etudinuit/2005/v29/n1-2/013942ar.pdf

Quinn S (2014, Oct. 23). Alaska’s indigenous languages now official along with English. Reuters. Retrieved from http://www.reuters.com/article/us-usa-alaska-languages-idUSKCN0ID00E20141024